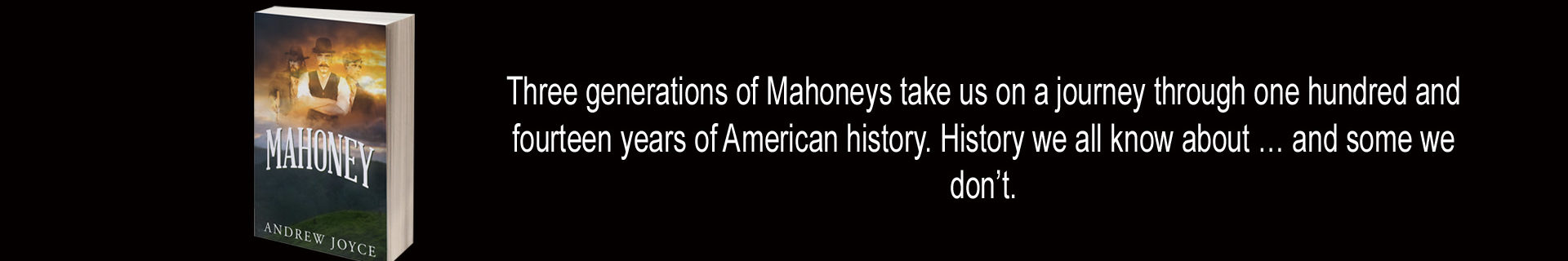

Chapter Two of Mahoney

You guys are sensational. You looked over my first chapter and made astute observations and suggestions. Some, I have already incorporated into the manuscript---others, I'm giving serious consideration to. I had not intended to post any more of the novel, but then I woke up this morning, I thought, Why the hell not? Getting input from as many people as possible before publication can only make my humble offering better. And don't worry. At the rate I'm writing, after the first five chapters, you'll be let off the hook indefinitely. I'm not working that hard. I'm too busy out smelling the roses, so to speak. And if I smell many more roses, my liver is going to explode.

By the way, the horrors you are about to encounter are real. Maybe the reason the book is going so slow is not my drinking. Maybe it's my research. For every ten minutes of writing I do, I spend twenty minutes in research. I'm not saying that is a good thing. Perhaps it's my way of avoiding that dreaded blank page.

If you remember, chapter one ended with my protagonist stepping out onto the road for his journey to Cork.

Chapter Two

An ancient road it was. The Roman Christians had used it in the fifth century to spread the Word and baptize an entire nation. Then it was the Danes, or Vikings as they were known, who had come to conquer the isle late in the eighth century, deepening the wheel ruts laid down by the monks. By the time the Normans arrived in the twelfth century, it was a well-worn track that led from Cork to the Western shore. Along its length, the Danes built their castles. In the sixteenth century, Henry the Eighth’s soldiers used the road in their subjugation of an unruly people. Three hundred years later, Devin Mahoney, in solitary desolation, followed the wheel-rutted lane to an uncertain future.

With a pale dawn approaching, Devin made his way east into the face of the rising sun. It was an exceptionally clear day—not a cloud in the sky. He saw no children playing on the side of the road as in years past. Occasionally he would pass a work gang, but for the most part he had the road to himself.

As he approached the town of Coom, he came across the body of a dead man right there on the side of the road. There was little doubt that he had died from starvation. The body was barely more than a skeleton. It was not the first dead person Devin had seen. Over that last fifteen months, he had seen many. Devin wore no hat to doff as he passed by, but he did nod in that direction as a sign of respect.

He made it as far as the outskirts of Glenflesk before deciding to stop for the night. He went into the woods off to his right while the last rays of the setting sun reflected off the somber grey clouds in the west, turning them a soft pink around the edges. He found a small clearing after a few steps. This will do, he thought.

The road followed the River Lee, so water was easily accessible. He had not stopped during the day to eat, for his strategy was to make what he carried in the sack last as long as possible. Besides, he was used to going without food. Nevertheless, he now eagerly anticipated a bowl of bland cornmeal or perhaps a little oatmeal.

He put the sack down and collected what dead branches he could find in the vicinity. After clearing a space for his fire, he snapped the thin wood into foot-long lengths and laid them on a small pile of dead leaves. Next, he reached into the sack for the matches. While rummaging around, he also brought out the small kettle and the larger of the two bags of food, figuring it to be the cornmeal.

Once the fire was going, Devin went to the river and drew a kettle half-full with water. On the way back to his camp, the thought suddenly struck him that Missus Meehan had made no mention of a spoon. How was he to eat his stirabout?

He need not have worried. Missus Meehan was a good woman, indeed she was. There was a large, wooden-handled spoon at the bottom of the sack.

With the meal mixed with water, he held the pot over the fire using a three-foot-long branch and waited for the concoction to start its contented bubbling. Then he would stir it, and before long, he would have warm food resting comfortably in his empty stomach.

Devin’s eyes were fixated on the dancing flames of the fire. They were mesmerizing. His body was warm, wrapped in the fine overcoat; his thoughts wandered. Little doubts silently crept into his contemplations. It was a long way to America. Did he really want to leave The Auld Sod? But if he stayed, what hope would there be for him? Half the country was slowly starving to death.

His thinking was abruptly interrupted by a thrashing noise behind him. Quickly he turned his head, but he could see nothing. He was blinded—he had been looking into the fire. In fear, he cried out, “Who goes there?”

A voice sang out, “’Tis only I, Tom McNevin from Kinsale, County Cork. I saw your fire and thought you might be wanting company on this grand night.”

When his eyes had adjusted to the darkness, he saw a man standing a few feet away, wearing a smile, his hat in hand. Devin relaxed. “Come in, Tom McNevin. Come and sit by the fire.”

McNevin squatted opposite his host and held his hands over the fire to warm them. The firelight reflected off his gaunt face, showing him to be about forty. His hair and beard were dark, but starting to turn a little grey. His eyes were laughing eyes—merry eyes. His clothes were little more than rags and he sported no overcoat—he wore no shoes. He looked across the fire at Devin and saw a young man with a sparse brown beard and stormy blue eyes. He was a good-looking lad and his welcoming smile made Tom McNevin feel right at home.

“’Tis a grand night to be sitting by a warm fire, such as yours, and in such in such fine company,” said McNevin.

“So ’tis. I’m Devin Mahoney.”

Devin noticed McNevin eyeing the pot he held over the flames. “Have you eaten recently?” he asked in a soft voice.

“I cannot say that I have. But I have not come to eat your food. ’Tis a cold night and your fire looked inviting.”

“You are welcome to anything I have. I too know what it is like to go without.”

Devin handed the stick holding the kettle to McNevin. “Here, take this. Keep it over the top of the flames. I’ll do the stirring and soon we’ll be eating like kings, we’ll be.”

As Devin gingerly stirred the cornmeal, he asked of McNevin, “When did you last eat?”

“Like many of our countrymen, it’s been a little while since a bit of food has passed these lips. A day or two days, ’tis all the same. Since the blight came upon us, one day seems like all the others. I don’t count time by days anymore or even hours. Time is the distance from one meal till the next.”

When the stirabout was ready, McNevin placed the pot on the ground next to the fire and eagerly looked in Devin’s direction. He was trying to be polite and wait, but the pain in his stomach willed him to inquire, “Do you have two spoons?”

“Only the one; you are my guest, you eat first. When you have had your fill, then I will eat.”

They took turns eating and when the pot was empty, McNevin insisted that it would be he that took it to the river and cleaned it. While he was at his task, Devin searched out more firewood. It was a cold night and they would have to keep the fire going. Devin would be warm enough in his heavy coat, but McNevin would need the warmth of a fire so as not to shiver throughout the night.

With things taken care of, the two men sat down next to the fire, one on each side, and looked into its flames. They were grateful to have eaten this evening. Their stomachs were full. Tomorrow would bring what tomorrow would bring. But for the moment, they were two contented Irishmen.

Without taking his eyes off the fire, Devin asked, “Are you going or coming from Kinsale?”

“I’ve been to Dublin. I’m going back to Kinsale, but there’s little of any worth there for me, no more. These days there is very little for me—and people like me—anywhere in all of Blessed Ireland.”

“You’re slightly out of your way.”

“When I left Dublin, I thought I’d roam a ways to the west and see if there was any work for an able-bodied man. I’ve been all the way over to Glenbeigh. There is no work—and very little food that I’ve come across in my travels.”

“I’ll tell you true, Tom McNevin, there is very little for us poor folks here in Ireland. The land of St. Patrick, fairies, and the little people. The land of ruins. Of standing stones that have stood since the beginning of time. The land where my ancestors vanquished the Danes and ruled all this land hereabouts. I tell you true, Tom McNevin.”

McNevin moved a little closer to the fire.

Devin threw on a few sticks to build it up. “Tell me, Tom. What is it like in a big city like Dublin? Are there hungry people there too?”

“If you are not ready for sleep, I’ll tell you what I’ve seen from Kinsale to Cork to Dublin and back. Me thinks that somehow we Irish have angered the gods. What misery I’ve seen. But I have also seen acts of boundless Christian kindness.

“Before I tell my story, you must tell me what it is that you are doing out here on a cold night, mixing stirabout and wearing a fine gentleman’s coat. I would think that you could afford to stay at an inn.”

Devin laughed. “The coat was given to me by a kind woman. Underneath, I am dressed much as you are.” He then told his story and ended it with, “I’ll be going to America now. When I return, I’ll live in as fine a manor house as you have ever seen and have a coach-and-four to draw me to and fro as befits a man of my standing. No longer will I be walking from town to town.”

McNevin warmed his hands over the fire. “I’m sorry about your family. Me, I never had much of a family. My mother died giving bringing me into the world and, for one reason or another, I never married. Perhaps it was for the best. I don’t know how I’d survive having my whole family wiped out in a trace.”

Devin shrugged and said, “My sister is safe up in the North.”

“’Tis good to hear,” affirmed McNevin.

Devin threw a few more dried branches onto the fire. “Now, you tell me what is happening outside of County Kerry, in the rest of Ireland.”

McNevin leaned back as the fire flared up. “I’ll get to telling you, to be sure. I am a seanchaí of renown. An Irish teller of tales am I. You make yourself comfortable and I’ll pay for my supper this night with a tale that you will remember and pass down to your grandchildren as they sit upon your knee in that fine manor house that you will one day be building.”

Devin pulled his knees up, wrapped his arms about his legs, and waited for the seanchaí to begin his story.

“I had six acres that I planted every year for twenty years. The crop fed me with enough left over to sell at market and keep me steeped in whiskey for a few weeks after harvest. My rent was always paid. But then the blight struck. The leaves withered, the stems rotted, and my beautiful praties were covered with dark and black patches. It all happened very quickly.

“Without a crop, my rent I could not pay. The owner’s middleman badgered me daily and told me I’d be thrown out onto the road unless I came through. This after twenty years on the same plot of land. I had always paid my rent, but would the landlord give an understanding to the blight and what it has done to this country? No, he would not. He wanted only his money and his tenant of twenty years be damned! I told the middleman that you cannot get blood from a turnip.

“As a result of the agent’s badgering, I took myself off and joined one of those work gangs that the government had set up. We went out at dawn each day to dig holes. There was no reason to dig those holes, but if we wanted to be paid, we’d have to dig them damn holes. The next day we would go out and fill in those very same holes. Sometimes we would build stone walls that enclosed nothing or made an existing wall higher by two feet or more. All for no rhyme or reason, only to keep us busy.

“At least we were fed twice a day. Once at ten and then again at four. But it was very poor gruel they gave us, it was. And you had to work the full ten hours to be given even that.

“At the end of the week, I would turn my pay over to the middleman to keep a hold on my farm. But he always told me I still owed. Finally, I had had enough. I was working ten hours a day, six days a week for two miserly meals a day. And after all that work, I still went hungry on Sundays!

“The summer of last year I gave up my farm and left Kinsale. I thought I could find work in Cork, loading boats. It was on my first day out that I saw my first horror. I came across a woman walking my way, holding a bundle in her arms. Like me, she was dressed in rags, and like me, she was thin, her face drawn. I could tell by her looks that she had not eaten in many a day. But unlike me, she had a look about her that I cannot describe.

“When we came abreast of one another, I stopped and asked, ‘Are y’ alright?’ She looked at me with a blank stare and says she, ‘I do be alright, but my baby is hungry. Can you spare a morsel of food for the wee little one?’

“I had a biscuit in me pocket that I was holding for dinner. How I could I say no to her plea even if I had wanted to? I withdrew the biscuit and held it out to her. She says, ‘You give it to him.’ She unwound the swaddling to reveal her child. It was horrible, it was. The infant was dead, and from the look of it, had been so for some time. I looked at the woman smiling down at the lifeless baby boy as though he was alive. She had lost her mind either from hunger or grief—or both.”

Devin exclaimed, “That is horrible. What did you do?”

“I did the only thing I could do. I pressed the biscuit into her hand, saying, ‘You feed him and have some for yourself.’ She did not try to feed her baby and she did not raise the biscuit to her mouth. So, the only other thing I could say was, ‘Mind yourself, mother.’ She thanked me and resumed her slow wanderings. I stood in the middle of the road watching until she was out of sight.”

“Yesterday, I came across a dead man lying in the road just outside of Coom,” volunteered Devin.

“Aye. Corpses lay thick upon the roadside these days. I’ve seen a few myself. A month back, I stepped into a burying ground to avail myself of a little shade from the beech trees lining its walks. There was a funeral taking place and I decided to linger until the service was over. After the mourners had left, the burying men held the coffin over the dug grave. One of them pulled a string and a spring mechanism popped open the bottom and the body wrapped in old potato sacks fell six feet to its final resting place. I asked about it. ‘We have run out of wood for making coffins—there are just too many dead,’ informed one of the men. ‘Undertakers all over Ireland are doing the same,’ said another.”

“Now tell me, Tom McNevin, what is life like in the cities of Cork and Dublin?” questioned Devin.

McNevin leaned toward the fire—his face a ghostly yellow from the reflecting flames—and said, “’Tis a little better than the country, but not by much. There is no work to be had in either place. People from the country have crowded the streets looking for work and the police do not like it. But they arrest no one because then they’d have to feed them. What they do is give beatings in an effort to drive them back to the country. I’ve been on the receiving end of a few beatings myself.”

“Do they beat the women also?”

“To be sure, I have seen it done, so I have.”

“Then glad I am to be going to America,” sighed Devin. “What else have you seen? I want to know so that I can tell the people of America the true story of what is happening here. They are a rich people, and a kind people. They would send relief if they only knew.”

McNevin threw a few more sticks onto the fire. When they had caught, and the flames danced about in the slight wind that was coming down from the north, he said, “’Tis to be a cold night this night. I am grateful for the warmth of your fire, and I will tell you of more things that I have seen. I cannot understand how we have fallen so low.”

Devin braced himself for what he about to hear.

“From Dublin, I walked west to Galway. ’Tis on the coast that I saw what cruelty really is. There were two women collecting seaweed and putting it into baskets. Having nothing better to occupy my time, I approached them with an Irish greeting, ‘Dia dhuit.’

“‘Hello to you,’ answered one of the women.

“They were both older than I, grey-headed, and dressed in rags. One of ’em had a ratty old red shawl about her shoulders. The other one’s dress was in such tatters that it was cut off above the knees. Both their dresses were heavily patched and neither of the women wore shoes.

“They continued with their work, picking up the seaweed below the high water mark, as we walked along the beach. ‘There be plenty of what you’re after just a few feet away, above the high water line,’ says I. ‘Why do you scavenge for the scraps when the bounty is within reach?’ ‘We dare not,’ said the one with the red shawl. ‘’Tis the landlord’s property above that line.’

“The wind was blowing in off the ocean and it felt good, being the warm August day it was. We walked in that manner for a short while, when, from the north, three policemen came running towards us, making heavy footprints in the sand.

“When they caught up to us, two of them pulled the baskets out of the women’s hands. There was a sergeant and two privates. The sergeant said, ‘I arrest you for thievery. You three are to come along with us. And come peaceably if you know what is good for you.’

“I was shocked at the turn of events. Not so much that I was being arrested, but by the fact that it was against the law to collect seaweed. Since when?”

Devin shrugged his shoulders.

McNevin answered the shrug. “I’ll tell you since when. Since those damn English came here with Henry II hundreds of years ago. Those damn English think they own the whole damn island and all of us too! But enough of that. Back to my story.”

Devin broke a dead branch in two and threw the pieces onto the fire. “Please continue,” he urged.

“The women told the police that they took seaweed only from below the high tide mark. ‘That is surely not against the law,’ pleaded one of the women.

“Apparently it was. The constable’s rejoinder was short and to the point. ‘One of the landlord’s drivers saw you and reported you. There is nothing that we can do here. You must face a judge in a court of law. But why were you collecting seaweed? You do not look like you have a crop that needs fertilizing.’

“‘We was gathering it to eat,’ said the woman with the torn dress. At that point, I spoke up. ‘I was not stealing seaweed. I was merely walking along with these two grand ladies, enjoying the smell of the ocean air and their good company. You do not see a basket in my hands.’

“The women corroborated my words. And the sergeant, being a fair man, said, “Seeing as how the report was about two women and there was no mention of a man, you be on your way now.”

“I wished the women well and continued down the beach until I came to a path that led back to the road. I’ll tell you true. There have been times since then that I wished I had allowed myself to be arrested. At least I would have been fed twice a day while in jail.”

Devin shook his head and said, “’Tis a sorry thing to hear.”

“Aye, it ’tis,” concurred McNevin. Then added, “But not as bad as seeing it.”

Devin fed the fire and said, “We should sleep. We have a good walk ahead of us tomorrow.”

“Are you saying you want me to travel the road with y’?” asked McNevin.

“Sure. You are my seanchaí. As we walk, you’ll be telling me tales of things you’ve seen in this last year and I’ll be sharing my food with y’.”

“It will give my head peace to travel with you. May your blessings outnumber the shamrocks that grow.”

“Thank you, Tom. There’s enough wood to sustain the fire throughout the night, but I’ll have to depend on you to keep it going. According to my brothers, I’m not very good at that sort of thing.”

“I’ll see you on the morrow, Devin Mahoney.”

“God willing.”