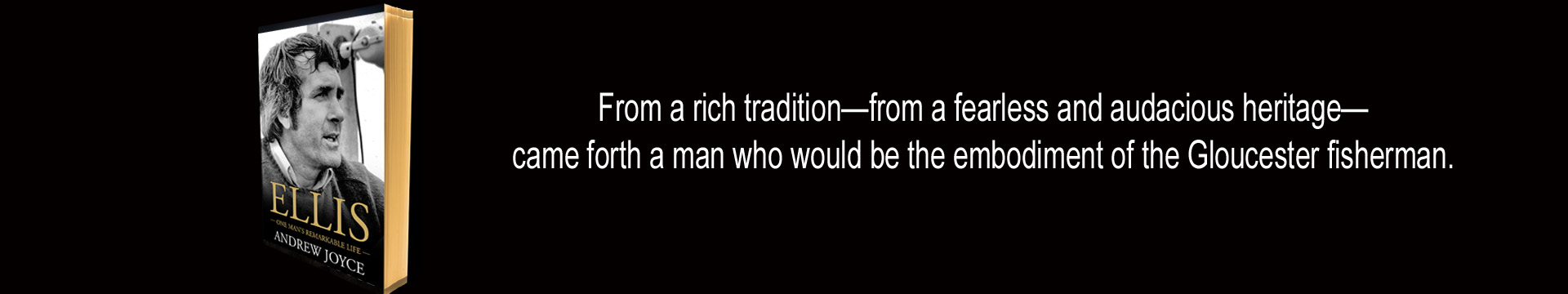

Remember, this is all true.

Chapter Six

“Hello. Is this Ellis Hodgkins?”

“Who wants to know?”

“My name is Dan Levin. I’m a writer for Sports Illustrated.”

“Sure you are.”

“Seriously. We would like to feature you in an upcoming issue.”

“Why in hell would you want to do that?”

“Word has come to us about your prowess when hunting the bluefin tuna. We’re planning an article about the demise of the fishing grounds and seeing as how you were the one who kind of got the whole thing started, my editor and I thought you’d be the person to talk to. It’s as simple as that.”

“How did you hear about me?”

“We have a mutual friend by the name of Myron Birch. He’s been telling me about the legend of Captain Ellis for a while now. I finally did a little research into you, and lo and behold, he wasn’t shitting me. So what do you say? You wanna be written up in a big-time magazine?”

“I’ll have to think on it. Give me your phone number and I’ll call you back.”

Ellis was pretty sure the phone call was a put-up job instigated by one of his friends. However, the number did have a New York City area code. He called back later that day and was a bit surprised when a professional-sounding woman answered. “Time, Inc. How may I direct your call?”

“I’d like to speak with Dan Levin.”

“Yes, sir.”

A moment later, Ellis was speaking to Levin, “I guess you’re legit. How do you want to do this?”

Three weeks later, Levin and a photographer from Sports Illustrated met with Ellis at the Cape Ann Marina.

Levin spoke first. “Mr. Hodgkins, this is Peter Balasko. He’s my photographer. The plan is that we will follow you around for a week. I’ll be asking you questions and Pete will be taking pictures. How does that sound to you?”

Ellis had one question he needed answered before things went any further. “Who’s picking up the bar tab tonight?”

“We’re on an expense account, Mr. Hodgkins. Wherever you go for the next week is on us.”

Ellis smiled and said, “So what do you want to know?”

“We’re here to learn about you and bluefin tuna fishing. While researching you, I came across an article written in the Gloucester Times. It was about the time when you were fourteen and you caught a 750-pound tuna with a hand line. Why don’t you tell me about that and then we’ll progress from there.”

“I had forgotten all about that.”

“You forgot that you landed a 750 pound tuna?”

“No … I forgot about it being written up in the newspaper.”

So, the men from New York stayed a week in Gloucester. Besides interviewing Ellis and people who knew him, at night they would follow Ellis to his favorite haunts and sit at a nearby table listening in on the talk of the Cape Ann fisherman and his friends. They never overtly intruded into his life, and for that Ellis was grateful. For his part, he never took advantage of the Sports Illustrated purse. Even though they picked up the tab everywhere he went that week, Ellis was restrained in his ordering. He bought a round for the house only once.

Levin gathered what information he could and Balasko took pictures he deemed appropriate for the article. Two months later, it appeared in the November 18th, 1974 issue of Sports Illustrated magazine.

The lead sentence read as follows: Ellis Hodgkins stands in his doorway, huddled against the wind, squinting out to sea with his one good eye.

When the article came out, everyone in town loved it and hailed Ellis as a hero—everyone, that is, except his mother. She did not like the fact that it mentioned he had only one good eye.

“Why did you let them write that about your bad eye?” inquired his mother.

“I had no say in it. And besides, who cares?” answered Ellis.

That was Ellis. He had one rule that he lived by. It was a simple rule. He never broke it and he never strayed from its fundamental precept. To quote Ellis, “Who gives a fuck?” Or as stated in his high school year book: The Boy Least Likely to Give a Good Gosh Darn. It was 1953 after all. That was as explicit as they could get.

One thing all the Sports Illustrated hoopla brought home to bear, at least for Ellis, was the fact that the days of catching bluefin tuna—at least in the way he had done it—were over. The article made note that Ellis’ charters had gone from one hundred eighty-two catches of bluefin in one season to thirteen within a three-year span. It was time to move on.

He put his boat up for sale and informed the owner of the Volkswagen dealership that he was leaving town. It was nothing personal, but he was looking for new horizons. And besides, he had grown tired of the car business. He gave a two-month notice. His last day would be July 4th.

Ellis was an employee any boss would want to keep around. He had once suggested that the dealership should stay open on Christmas Eve.

“Maybe we can sell a car or two.”

“I can’t get any of the salesmen to stay here on Christmas Eve,” replied the owner.

“No need to. I’ll do it. You never know. Maybe someone will want to buy a car for a last-minute Christmas gift.”

Shaking his head at the dedication of his employee, the owner said, “Forget it, Ellis.”

A little while later, when Ellis started to get restless and make noises like he might be ready to move on to another profession, the owner handed him a blank check and told him to go get himself a boat. Ellis had sold the Cape Ann the previous fall.

“Go and do a little fishing and then come back.”

“How much do I spend?”

“Just get a boat that you like, catch yourself some damn fish, and then come back here and sell some cars for me.”

Now, two years later, here was Ellis announcing he was definitely leaving, the owner didn’t think anyone being paid as much as Ellis was would ever give up that kind of money. For the next sixty days, every time he saw Ellis, he would say, “You’re not leaving.” And every time Ellis would respond, “Yes, I am.”

On July 3rd, his boss observed him packing up his things and said to Ellis in a resigned voice, “I guess you are leaving.”

“I guess I am,” responded Ellis.

In the hopes that he would return, the dealership sent him a paycheck every week for one year and they kept him on their insurance program for the same amount of time. Ellis would call his ex-boss periodically and implore him to stop sending the checks. However, they kept coming every week for fifty-two weeks straight. Even long after Ellis had moved far from Gloucester.

His many friends and acquaintances threw him a going-away party, the likes of which were seldom seen in that neck of the woods. It was a massive affair—standing room only. Half the town showed up. Two days later, he packed up his conversion van and his current lady friend, Karla, and headed south.

Act II of Ellis Hodgkins’ life is about to commence.

Chapter Seven

His village sits at the mouth of the Touloukaera River. Touloukaera means life giving in the Tequesta language. Aichi is awake early this morn. It is still dark as he paddles his canoe across the short expanse of water that leads to the barrier island to the east.

Today he will build three fires on the beach for the purpose of giving thanks to Tamosi, The Ancient One—the God of his people. The fires must be lit before the dawn arrives. It has been a bountiful season. The men have caught many fish and killed many deer. The women of his village gathered enough palmetto berries, palm nuts, and coco plums to last until next season. There is an abundance of coontie root for the making of flour. Tomosi has been good to his people.

Tonight, the entire village will honor Tomosi. But this morning, Aichi will honor Him in a solitary way. Because tonight, at the celebration, he will wed Aloi, the most beautiful woman in the village. It took many seasons to win her heart, and now he must acknowledge Tomosi’s role in having Aloi fall in love with him.

He builds three fires to represent man’s three souls—the eyes, the shadow, and the reflection. When the fires are burning bright and the flames are leaping into the cool morning air in an effort to reach Tomosi, Aichi will face the ocean. With the fires behind him, he’ll kneel on the fine white sand and lower his head until his forehead meets the earth. He will then start to pray and will continue with his prayers until the sun rises out of the eastern sea. At that time, he will ask that he be shown an omen that his prayers have been heard.

The first rays of the awakened sun reflects off the white sand. Aichi raises his head and there before him is the sign Tomosi has sent him. Not a mile away, floating on the calm, blue ocean are three canoes of great size. He can see men walking on what looks like huts. He knows they are sent from Tomosi because they each have squares of white fluttering in the light breeze. White denotes The Ancient One. And if that were not enough, no men paddle the massive canoes. They are moving under their own power, traveling north to the land where Tomosi lives. The men upon those canoes must not be men at all. They are the souls of the dead being taken to the heaven of the righteous.

Aichi leaps to his feet and runs along the shoreline trying to keep abreast of the canoes. But in time, he falls behind and soon they drop below the horizon. What a wondrous day this is. He has communed with his god and tonight he will wed Aloi. With joy in his heart, Aichi runs back to his canoe. He must tell the people of his village what he has seen.

What Aichi has seen are not spirit canoes. They are three ships from the fleet commanded by Juan Ponce de León. He is sailing along the coast of a peninsular he has named Florido which means “full of flowers.” He is in search of gold to bring back to his king. He has also heard from the Indians to the south that somewhere to the north lies a spring of clear water that if one drinks from it, one would have eternal youth. To bring a cask of that water back to Spain would make him a rich man indeed. The year is 1513 A.D.

Aichi and Aloi produce many children and grandchildren. But to no avail. The coming of the Spaniards has decimated the Tequesta. Most have died of the diseases brought by the white man. Others were captured and sold into slavery. By the year 1750, the village by the river that celebrated Tomosi’s largess in the year 1513 is abandoned and overgrown with plant life.

In the spring of 1788, the Spanish drive the Creek and Oconee Indians south to the land once populated by the Tequesta. The Spanish refer to the bands of Indians as Cimarrons, which means Wild Ones. The Americans to the north bastardize the name and call the Indians, Seminoles.

In 1789, a band of Seminoles, tired of running from the Spanish, inhabit the place on the river where the Tequesta once lived. They name the river, Himmarasee, meaning “New Water.” They live in relative peace for twenty-seven years. But at the outbreak of The First Seminole War, the Seminoles move their village farther west and into the Everglades to keep out of the white man’s reach.

In 1821, Spain cedes Florida to the United States, and the Americans begin surveying and mapping their new territory. Over time, the shifting sands of the barrier island caused the mouth of the river to empty into the Atlantic Ocean at different points along the coast. As the coastline was periodically charted, the surveyors—not understanding the effects of the shifting sand on the river’s behavior—thought that the various entry points were “new” rivers; hence, each time the land was surveyed, the map makers would make the notation “new river” on the updated chart.

The 1830 census lists seventy people living in and around the “New River Settlement.”

In the year 1838, at the beginning of The Second Seminole War, Major William Lauderdale and his Tennessee Volunteers are ordered to build a stockade to protect the settlers along what has become known as The New River. He selects a location of firm and level ground at the mouth of the river where once the Tequesta and Seminoles had built their villages.

The fort is decommissioned after only a few months. Two months later, the Seminoles burn it to the ground. The fort is now gone, but the name remains.

There are no roads into Fort Lauderdale until 1892, when a single road linking Miami to the south and Lantana to the north is cut out of the mangroves. In 1911, Fort Lauderdale is incorporated into a city.

During the 1920s, there is a land boom in South Florida. Everybody and his brother is buying land. When the most desired land runs out, developers make acres of new land by dredging the waterways and using the sand and silt thus obtained to make islands where future houses will one day stand.

Because of its natural geography and the dredging that went on in the ’20s, Fort Lauderdale has become known as the American Venice. There are countless canals, both large and small. Most houses on those canals have a boat tied up behind it. And many of those who do not live on a canal have boats sitting in marinas or sitting on a trailer in their backyards.

In 1974, twelve percent of the population of Broward County, in which Fort Lauderdale lies, make a direct living off the boating industry. Another twenty percent benefit indirectly.

Into this world Ellis Hodgkins descends … trailing Karla in his wake.

https://plus.google.com/+AndrewJoyce76/posts/Lte2VVRVNTE

Fabulous, Andrew. Nothing much else to say.

Looking forward to Chapter 8… I echo John!

Gosh darn… I like this guy

Terrific piece of writing, Andrew. You always pull me in…

Fabulous!!

Reblogged this on Chris The Story Reading Ape's Blog.

Thanks, Chris.

Welcome, Andrew 😀

Hi Andrew,

I’m enjoying the series and l’m always fascinated with your writing. BTW Merry Christmas.