Year: 2014

Going Home

I'm on my way ... I'm on my way home. I've spent so many years getting here. I'm writing this on the fly ... no editing ... no nothing. I drink too much I don't understand why. I'm always half stoned. I'm always looking at what God has wrought. Even in my cups, I see the beauty ... I see the wonder ... I see myself in my Father. I see our Father in you ... I see our Father in the plants and in the trees . . . I see our Father everywhere . . . and goddamn it . . . and GODDAMN ME! ... I even see our Father in Dick Chaney.

Danny Trains Andrew (Again!)

Man oh man . . . did I have a restful sleep last night! Well, truth be known, the best part of my slumber was from 6:00 AM to about noon.

Hello fans o’ mine. It is I, Danny the Dog, here once again to regale you with my adventures.

I’m sure most of the planet knows me by now, but for those of you who live in the rain forest of Borneo, whenever the spirit moves me, I write about my adventures with my human. His name is Andrew and if he didn’t feed me every night, I wouldn’t mention him in my communiqués at all.

You all know how well trained Andrew is. He is so well trained, that life has become somewhat boring. So about a week ago, I decided to spice up my life by throwing something new into the mix. And it turned out to be so much fun.

You see, Andrew is very, very indolent. If it were up to him, he’d live like Jabba The Hut. I mean stay in bed all day, I don’t mean have a girl on a leash. Well, maybe if he could get away with it, he’d keep a girl on a leash. Why not? He keeps me on a leash!

Anyway, now to the fun part of my story.

Because Andrew is so lazy, he likes to sleep at least till mid-morning. I don’t really mind, I like to do the same; however, a week ago, I came up with a brilliant plan, if I do say so myself . . . and I do.

At this juncture, I must digress for a moment. You see, although I tolerate Andrew, I do not like sleeping with him. During the day, I have the bed all to myself, unless the lazy so-and-so decides to take a nap after a full day of doing nothing. Then I sigh, get up and go out to the galley (kitchen to you landlubbers). I like the floor there. It’s nice and cool. And of course, at night I sleep there. It’s better than sleeping with Andrew. Anything is better than sleeping with Andrew!

Okay . . . back to our story . . . already in progress.

This is now our life together. I wake up somewhere between 4:30 and 5:30 AM and start a low growl in the back of my throat. Then I start wagging my tail so that it hits the wall. The THUMP, THUMP, THUMP is enough to rouse the dead, let alone Andrew.

When I first started doing this, Andrew thought I wanted to go outside, so after cursing me under his breath (don’t think I didn’t hear that Andrew!), he would get out of bed, get dressed and open the door. Then he would stand there waiting for me to run out so I could do my “business.”

Instead, I made for the bed and stretched out, hogging it all for myself. This went on for a few days until Andrew got hip. But with the growling and tail wagging, he can’t sleep anyway. Now he is trained to get out of bed at my command and then I have it all for myself. He doesn’t mind too much. He says that at least he can get a little writing done while I’m sleeping. Whatever that means.

I’m allowing him the bed as I write these words. But in a few minutes, I’ll get him up and tell him to go to work. Someone has to write his stupid books, and I’m sure as hell not going to do it.

So that’s it. Not a heart-pounding story this time, but very informative if one wants to train one’s human.

http://huckfinn76.com

My Girl

I come from the projects. I ain’t no softy. In fact, I’d just as soon slit your throat as look at you. They have me now . . . I was stupid enough to get caught after that gas station robbery. What was the big fucking deal? We got only forty bucks. The cops came a-shootin’. My man, Daryl, took a bullet to the head. Under the man’s law, I was charged with murder in the second degree because someone died in the commission of a felony. How do you like that shit? The cops didn’t have to shoot, we were not armed. Of course, I was convicted. It was an all-white jury. What else can a black man expect in America?

Now I am looking at twenty years to life. I sit in my cell and think of my girl. Her skin is light brown and her smile used to send me to heaven. But I can’t see her smile no more. Her name is Gloria. She was my life. Now my life is trying not to get shived in the food line.

Gloria has written me, asking to visit. I will not allow it! I do not want her to see me in a cage. I wrote her back and told her to forget me. Get her a man as unlike me as possible.

It really doesn’t matter anymore. I will not live my life in a cage. Big Dog runs the blacks in this place. He is big, I’ll give him that. We are in the yard . . . the whites are on the far side … the spics opposite. And us niggers have the middle.

I rush at Big Dog looking like I’m holding a shive. I’m not. One of his lieutenants cuts me down before I can get close.

As I lay on the grass of the prison yard, my blood pooling beneath me, I think of my girl and of all the wrong choices I have made in my twenty years of life. But that’s cool . . . there are no more choices that have to be made unless you want to ask me how deep I want to be buried.

Just for the record, it’s six feet.

http://huckfinn76.com

TREASURE

He stumbled upon the treasure quite by accident. He was exploring in the vicinity when he happened upon it. His first thought was, “This cannot be real.” He approached it gingerly, not sure if it was not some kind of trick. Someone might be observing him right at that moment, and if he were to get near the treasure, spring out of their concealment and brand him a thief. But no one sprung from a concealed location, no one yelled for him to halt his advance. It seemed safe to move forward. When he arrived at the treasure, he bent down to touch it, just to make sure it was real. After one touch, he fled to better-known and safer environs.

That night he could not sleep for thinking of what he had discovered. He thought and thought of ways he could explain it to members of his tribe. If he suddenly showed up with the treasure, anything he said would be suspect. One does not find treasure of this sort every day. No, he would have to think this through.

The next day he went to the area of the treasure, but dared not get too close. Instead, he peered at it from a distance. It was still there, and untouched! For how long would it stay undiscovered? A fire burned within him to possess it. If not for the taboo placed on matters of this sort by the Law Giver, he would claim the treasure as his own. But no, the Law Giver would never allow it.

The second night after the discovery, as he tried to sleep, he thought perhaps the Law Giver would understand. Maybe he should approach her. Tell her of his find. No . . . then if she forbade him from keeping the treasure, it would be lost forever. Conceivably, he could bring it to his village and hide it from the Law Giver. However, where could he hide it? The Law Giver knew all.

Then he overheard the Law Giver speaking of the place he had found the treasure. “When they moved out, they told me they left a few things behind and if we wanted anything we were welcome to it. I’ve been too busy to go over there, but I think I’ll take a look this afternoon. Maybe there will be something Joey might like.”

Something he might like. Something he might like! Was she toying with him? Did she indeed know of the treasure? Later that afternoon, his mother called Joey to the front of the house. He was not allowed far from home because he was only five years old. He appeared right away. His mother said, “Look what I found next door where the Simms used to live. And there it was, the treasure!

His mother handed little Joey the bright red, toy fire truck that has caused him so much anguish. You see, even though it seemed to have been abandoned, Joey was afraid his mother would think he had stolen it. And in his home, stealing was the one thing his mother, the Law Giver, would never tolerate.

http://huckfinn76.com

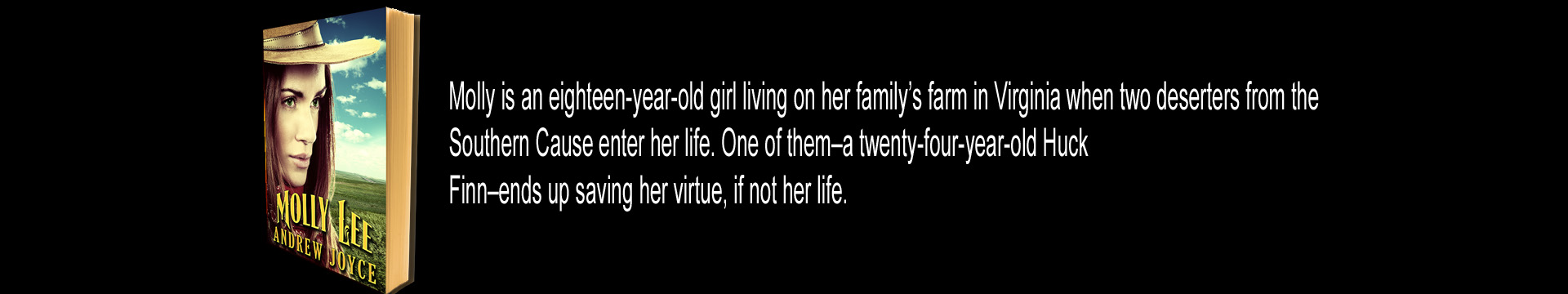

An Excerpt from MOLLY LEE the Sequel to REDEMPTION

That’s the way things stood for the next month. Business increased a little, partly due to my promoting myself as The Spicy Lady and partly because the snows had come. The miners could not work and had to sit on their claims throughout the winter or someone would take them over. I heard that last year a few miners had left for the winter and when they came back someone was sitting on their claims. It led to a little gun play with the one that was faster on the draw ending up with the mine. So with the miners not mining, there was nothing for them to do but go to a saloon and warm their insides with whiskey or their outside with one of the whores . . . or both.

I had made no progress with John Stone. He was always polite enough, but that’s as far as it went. It was on a Tuesday night—not that the day of the week matters—that I finally worked up the courage to make a play for John Stone. As usual, he was sitting in his chair watching the room. Over the last few weeks there had been a few minor altercations, but John always kept things peaceful. Sometimes it took a blunt knock to someone’s head with the stock of his shotgun and sometimes it took pointing the ten gauge in someone’s face. Both methods seemed to work equally well.

I walked over to him and just to make conversation said, “If you ever have to discharge that thing, won’t you hurt innocent people?” I was talking about the shotgun.

He didn’t say anything for a minute, then he let fly with a stream of tobacco juice out of the side of his mouth, and I’ll be damned if he didn’t hit the spittoon sitting next to his chair dead center. Without taking his eyes from the room, he answered me. “It’s just for show. If you point a ten gauge at someone, most of the time they’ll do what you say. If they don’t, and I ever have to shoot someone, I'll use this.” He then touched the Dragoon Colt on his hip.

I had just asked him if I could buy him a drink at the end of his shift when a ruckus broke out over at the faro table. When I turned around to see what all the commotion was about, I saw a man holding a revolver on Chan Harris. “You’ve been cheating me all night. I’ve lost my poke to your double dealin’ ways and now I want it back!”

Chan shrugged and started to count out some gold coins, after all it wasn’t his money, it was mine. He’d give the man his money back and let me worry about it. Smart thinking on his part. But I reckon he wasn’t counting fast enough to suit the man holding the gun. The shot, when it came, made all those within the room jump. All, that is, except John Stone.

Chan started to fall to the floor and the other two men at the table dove for cover, as did everybody else in the room except John and me. Before Chan hit the floor, John had the Colt out of its leather, and from his hip put a bullet into the gunman’s heart. Of course, it entered from the back, but no one was complaining, least of all the dead man, bleeding onto my floor with two twenty-dollar gold pieces clutched in his right hand.

When the smoked cleared, John said, “I reckon I could use a whiskey after work.”

I ran over to where Chan lay and knelt down to see what I could do to help him, but he was already dead.

The place cleared out fast, but some stayed and formed a circle around Chan and me. I was still kneeling next to him and I looked up into the hard faces of the men who stared back at me. And I saw nothing. To them, death on a Tuesday night was just another night out on the town.

I had seen dead men before. There were the two Yankees back at the farm. And Mister Fellows died in my arms. I wore his blood on my shirt until the shirt was taken away from me by Moon Woman. I don’t know why, but Chan’s death affected me more than the others had. Maybe it was because after finding the gold and buying The Spicy Lady, I thought my life would calm down some. Now here I was kneeling over another dead man. A man I didn’t even know that well. But he worked for me and I thought I should have done better by him. He should not have died making money for me.

I stood up and wanted to tell those still present to leave, but the words would not come. I started to shake and I felt like I was about to scream when I felt a strong hard arm around my shoulder and heard a voice, a surprisingly gentle voice seeing as who it came from, say, “You boys best be getting on, we’ll be closing up early tonight.” No one ever argued with John Stone unless they were drunk, and no one was drunk after seeing Chan Harris killed.

John took over. When the place was empty except for those that worked there, he told Dick and Dave to carry Chan into the back room and lay him out. He told me to go to the bar and have Abe pour me a water glass full of rye and then drink it.

I couldn’t stand up much longer, so I took my rye to a table and sat down. John was standing over the man he had killed, thinking. I don’t know what he was thinking, but at that point I didn’t care. I was supposed to be a hard woman, and here I was going to pieces. If we hadn’t been snowed in, I would have gotten on my horse that very minute and headed back to Virginia to be held in my mother’s arms, Hunts Buffalo be damned!

We didn’t have any law in town. There was no marshal or sheriff. We didn’t even have a mayor. When Dick and Dave came back from laying out Chan, John told them to pick up the other man and throw him out onto the street, then go to Chan’s digs and see if there were letters or anything to tell us if he had any next of kin then go home. He told Abe and Gus to leave by the back door and lock up as they usually did. As I’ve said, no one ever argued with John Stone. They all did as they were told.

From the time John took charge is a blur. Somehow he got the place closed up and came over to where I was sitting. He was holding the cash box. “I reckon you’ll want to put this in the safe before you go to bed.”

I looked up at him and started to laugh. I was getting hysterical. John nodded and went into my office. When he returned he said, “I put it on your desk, it’ll be safe enough.” He held out his hand and I took it. He pulled me to my feet and without saying a word, he walked me upstairs.

That night John Stone held me as I cried for Chan Harris . . . and maybe a little for myself.

http://huckfinn76.com

Danny Feels Sorry for His Fans and Writes a New Story

Okay girls! I know you’ve missed me and I have missed you. But please, stop sending me letters, emails and videos begging me to write some more of my adventures.

Wait, let me back up for a minute. For the few humans on the planet who don’t know who I am, allow me to introduce myself by paraphrasing Mick Jagger. I’m a dog of wealth and fame . . . my name is Danny the Dog, a heartbreaker to all females . . . human and canine alike.

Now back to business. You girls are in luck; I have a new adventure for you.

My latest exploits started on a dark and stormy night. (Wouldn’t you know it?) My human was at the computer pulling his hair out because he had been editing his latest book. That’s the reason I haven’t been writing. My human, whose name is Andrew, and I share one computer and he was hogging it. I was going to bite him, but he is my sole source of food.

Anyway, after two years of writing and research and four months of editing nine to ten hours a day, seven days a week, ol’ Andrew was coming apart at the seams. It wasn’t all the work that was getting him down, although he is very indolent. It was the fact that he thought no one would ever read his genius work. (His word, not mine.)

So just before he fell apart completely. I gave him my one-bark command and I took him for a walk to calm him down. When we returned to the boat, I hopped up on the bench in front of the computer and wouldn’t make room for him. (See accompanying photo.)

I barked at Andrew, telling him to go to bed. Then I stayed up throughout the night fixing his mess for him. And I must say that I’m hell-on-wheels when it comes to writing.

When I was finished saving his career (career?) I went into his email account (I know all his passwords) and emailed the now genius work to his agent.

If he had emailed the book like he had it before I got to it, you would never have heard from Andrew Joyce again. But with my paw prints all over it, look for it on the New York Times bestseller list any day now. And when they make it into a movie, I’m going to play Rin Tin Tin! (I wrote in a part of a hero dog just to give his stupid story some credibility.)

Well folks, that’s it for this go-round. Now that I have more access to the computer, look for my next modest adventure: Danny the Dog Saves the World! As are all my adventures, it is 100% true.

Night Moves

They are always with me. At times, they appear out of the ethereal mist and at other times they speak directly to my mind. I wish they would leave me to myself, but that they will not do. No, first I must do their bidding.

They come at night and stay until the black sky fades to gray. When the stars leave the sky and the clouds to the east turn pink, I am allowed to rest. But I ask you, what respite can a murderer have? At their behest, I have killed again this night. And I will continue to kill until they go back from whence they came.

I remember the first time they came to me. It was a little over a year ago and since then I have killed twenty-nine people. Please do not think me insane. I assure you these beings are real and are not immanent. At first, I too thought myself demented when they stood before me telling me they came to save the human race, and to accomplish their mission certain people must die. They explained that the demise of the race was not imminent, but if action was not taken, and taken soon, it would be too late to set things on a course to ensure the continuance of mankind.

You are probably wondering, if you do not think me crazed, why they cannot do their own dirty work. And it is a good question, one I have asked. They, of course, are not of our time and space. They appear, when they appear, as diaphanous specters, they cannot manipulate physical matter. Thus I have become their instrument here on earth. Where or when they are from I do not know. And why, out of all the billions on this planet I was chosen, I know not. But it has been a long night and I must sleep. I will continue this at a later date, and continue it I shall, for I want there to be a record of my actions and the reasons for them.

I am back. It has been two days since my last entry, and tonight they had me kill again. That makes thirty people, thirty innocent people—men, women and children, I have dispatched from this world. Yes, I am sorry to say that they have had me kill children. However, I was told that after tonight there would be no more need of my services, the human race was safe for the foreseeable future.

I refer to my tormentors as they or them because I do not know what they call themselves. Their form is vaguely human, two arms, two legs, and a head of sorts atop a torso, but their gossamer appearance precludes calling them human.

Tonight’s victim was a man in Moscow. I was directed to him and given his name. I then set about their business. I was told that his son, yet unborn, would one day invent something that would cause the death of billions. Being told the basis for this particular death was a departure from the norm; I had never been given rhyme nor reason for any of the others. The man’s name and the names of the other twenty-nine, with where and when they died, are in the addendum attached to this missive. I remember every one of my quarry.

I guess I should have mentioned this earlier, but my victims were scattered around the world. I do not know how they did it, but one minute I was in my room behind a locked door and the next minute I was standing in a foreign locale with the name of that night’s victim swirling through my brain. Then into my mind came the place I could find him or her in the city, town or hamlet.

Now, the thirty-first person will die. They, at last, have left me to myself. I am now free to end this the only way it can be ended, with my death. I’ve been saving and hiding my medication for quite a while now, there is enough to kill me three times over. May God have mercy on my soul.

I affix my hand to this document this 30th day of June in the year of our Lord 2011.

Signed,

Francis Fitzgerald

When Dr. Allen had finished reading the above, he turned to Dr. Harris and said, “Interesting, but why have you brought it to me? We both know that the man was a certified, delusional schizophrenic. How long have we had him here at our institution?”

Dr. Harris hesitantly answered, “He’s been here at Oakwood twelve years sir.”

“Well there you have it. It’s too bad he took his own life, it doesn’t help our reputation any, but these things happen.”

“Yes sir. However, there is something I think you ought to know.”

“Yes?”

“I’ve taken the liberty of investigating a few of the names on Fitzgerald’s list. It’s taken me three weeks, but I’ve verified eleven of the deaths and their time and place. They all correspond with what Fitzgerald has written.”

Dr. Allen straightened in his seat, glanced at the papers in his hand, and then looking Dr. Harris in the eye, very forcibly said, “Preposterous! If there is any correlation, he read of the deaths in the newspaper or heard of them on the television.”

“Excuse me sir, but Fitzgerald had no access to newspapers. He was denied them because they would agitate him to no end. And the only television he had access to was in the day room where the set is perpetually tuned to a movie channel.”

“That still does not give credence to this fairytale,” said Dr. Allen waving the Fitzgerald papers at Dr. Harris.

“No sir, it does not. However, there is one thing I think I should make you aware of. My sister is married to a Russian physicist, speaks fluent Russian and lives in Moscow. I called her about the last name on Fitzgerald’s list. She made a few calls for me and it turns out that Fitzgerald was dead before the body of the man he mentions was discovered. And just one more thing sir, the man’s wallet was found in Fitzgerald’s room. I have it if you’d like to see it.”

Turning a color red that is not in the spectrum, Dr. Allen shouted, “NO! I DO NOT WANT TO SEE THE DAMN WALLET!” And then handing the Fitzgerald papers to Dr. Harris, he said with ice in his voice, “Burn these, burn them now. And if you value your position here at Oakwood you will never speak of this matter again, to anyone. Do I make myself clear?”

Dr. Harris accepted the papers, and with a meek, “Yes sir,” walked out of the room. When he was in the hall, and by himself, he let out with a, “I’ll be goddamned, the old bastard is afraid.”

But Dr. Harris did not burn the papers. He placed them, with the wallet in his desk drawer and then locked it. He had some thinking to do. And as he started on his rounds, a quote of Shakespeare’s kept repeating itself in his head. “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, then are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

The Denéé

The People:

It was my second-and–a-half-year of being on the road when I met Jimmy of The Denéé. I had left home at seventeen by coning my mother into allowing me to “attempt” to hitchhike to California. I told her no one was going to pick me up anyway, and after an hour or so I would be back home; so please just let me get it out of my system. I did not make it home that day; within minutes of sticking my thumb out, I got a ride. I knew I wanted to get to California, but had no idea which roads to take, so I just went anywhere the ride was going as long as it was in a generally western direction. This was before the Interstate system was up and running. As a light breeze carries a leaf upon on a current of air, I allowed myself to be taken wherever the cars that picked me up happen to go. I ended up in Peoria Illinois on Route 66. Yes, I did travel that fabled highway on my very first foray into the world. Gallop New Mexico, Flagstaff Arizona, San Bernardino; I got hip to that kindly tip and I got my kicks on Route 66.

That was more than two years ago. This day I was standing on the side of US highway 90 in the State of Arizona, heading east. My thumb in the prerequisite position awaiting the chariot that would get me that much closer to home, yes, I was going home. Of course I had kept in touch with the family, but at nineteen I was a bit weary of going hungry, sleeping on the side the road; and when tired of hitchhiking, being thrown out of box cars in freight yards by the “bulls.” Little did I know that the next ride I got would delay my homecoming by another two years.

It was late in the day, about two hours before the sun went down, which in the summer, in the desert, meant the time was about 8:00 pm. Just then, an old blue, broken down pickup truck stops with three men and a woman in the cab, they were squeezed in like the proverbial sardines of old. The guy hanging out the passenger side window yells, “Jump in,” meaning of course the bed of the truck. At that age I was good at following orders, so I comply with the command and hop over the tailgate; before I can get settled, the truck takes off, spurring rocks and pebbles in its wake.

I ensconce myself up against the cab facing backwards. As I get settled, I noticed the bed of the truck in which I’m riding is littered with half pint bottles of O’Neil’s Irish Whiskey, there must have been a hundred or a hundred and fifty little bottles lying on the floor of that truck.Well, I think to myself, I see some Irish did make it this far west. My people hadn’t made it west of the Charles River in Boston. As a mick, it did my Irish heart good to know I was riding with some Irish cowboys. Boy was I wrong!

After about fifteen minutes the truck made a left off the paved road and I peeked around the cab to see where we were going. It seems we were going nowhere; they had pulled off onto an unpaved road, no, it was more like a wide trail. My friend, who originally told me to get in the truck, leans his smiling face out the window and says, “It’s getting late, want a place to stay the night?”

Now ordinarily hitching at night is no big deal, but as I looked at the deserted road we had just exited, coupled with the fact that it gets mighty cold in the desert at night, I meekly said, “Yes thank you.” With that, the driver hit the accelerator and off we went. This “road,” not being paved, was a bit hard on the old backbone, so I had to retrieve my sleeping bag and use it as a cushion between my rear end and the floor of truck.

Still facing backwards with my back against the cab, I had a vey nice view of where we’ve been, though I had no idea of where we were going. After I had settled down, and gotten more or less used to the jostling about, I heard a ringing sound, no it was more like the sound of chimes that were very far away. “What the hell is that,” I thought. It took a few seconds for me to realize the sound was coming from the floor of the truck; it was all those whiskey bottles. The fact that they were touching one another, and vibrating was causing them to make music! The tintinnabulation was in perfect harmony, which would build to a crescendo before settling down to the soft chimes I had first heard. Those empty whiskey bottles did indeed make the ringing sounds of many small bells. I’m loathe to use the word mystical; however, there is no other word that comes to mind to describe the music those whiskey bottles played for me as I was bounced around in the back of that pickup truck. And that was not the only mystical experience in store for me that evening.

After what seemed a very long time we exited the trail onto a smoother road, though still unpaved. In a few minutes the truck screeched to a stop. The person who had done all the talking got out and told me that this was it, and I might as well get out too. No sooner had I hit the ground then the truck lurched forward and the guy standing on the street with me had to jump back from being sideswiped. “Damn drunken Indians,” he shouted as the truck disappeared in a cloud of dust of its own making. It was then that I noticed the man standing in front of me was a full-blooded American Indian, or as is the custom of today, a Native American. He was slight of build, not much older then me, and had the most infectious smile I have ever seen on another human being.

After a half hearted attempt at dusting himself off, he looked at me, smiled and said, “Hi my name’s Jimmy.” And then he asked me my name. After I told him, he inquired if I had ever been on an Indian Reservation before. When I told him I had not, he said, “Welcome to Fort Apache Indian Reservation USGS Cedar Creek Quad, Arizona.” He then added to himself, and more as an after thought than anything else, “Quite a mouthful for a two million acre dump.”

He told me they always come in the back way because, “The Tribal Police are such a pain in the butt, always messin’ with people just because they can.”

When I heard the words, “Indian Reservation,” I looked around and saw no teepees, no hogans and no wigwams. The only structures I did see were squat, little adobe buildings that were about six feet high. Jimmy pointed to the one in front of which we were standing and said, “Home Sweet Home.” He then told me to get my gear, and suggested we get out of the street before some drunken Indian ran us down. He walked over and held the door open for me, telling me to leave my gear outside for now. As we entered, we both had to duck our heads so as not to strike them on the lintel of the door.

The first thing I noticed upon entering Jimmy’s home was an old lady who seemed to be preparing a meal. She looked up and said, “How dah.”

“That’s my grandmother,” Jimmy said. He then added, “She welcomes you to come in.” He explained as we were getting settled that his grandmother spoke no English. The only piece of furniture in the room was a low table in the shape of a rectangle about eight feet long and four feet wide. It sat about two feet off the floor, and situated around the table were mats, which were positioned on the floor, three to a side and one at each end of the table. Each mat was two feet long and two feet wide. The only other thing in the room that could conceivably be called furniture was the counter where Jimmy’s grandmother was working. It looked like it was built into the wall, supported by two legs, one at each end. Oh yeah, there was an old fashion wood stove in the far corner, but I did not consider that furniture. Jimmy pointed to a mat and said, “Sit, dinner will be ready shortly.”

I sat on one side of the table and Jimmy sat opposite me. I thanked him for his hospitality and asked him to thank his grandmother for hers. He asked me where I was going and where I was coming from. I didn’t go into details, I just told him I was traveling from California to Miami, which was my home. When I said Miami, he did a double take.

He said, “Why that’s just down the road,” and added, “You could have walked there.” He was right there is a Miami Arizona only a few miles from the Reservation. I apologized for being inaccurate or incomplete with my words and told him it was Miami Florida, which was my home.

When I said that his smile, which seemed to be continually on his face, broadened even more as he said, “Hot damn that’s right there are two Miami’s.” I had to inform him that there were at least three that I knew of, the third being in Ohio. Jimmy got a big kick out of that. He had me talking about myself for about half an hour before I wised up and said, “Jimmy, you’re a great host, you got me yappin’ about myself when it’s I who should be asking you the questions. You know, you’re the first real Indian I’ve ever met.”

And with a twinkle in his eye Jimmy asked, “Really how many fake Indians have you met?”

“Okay, okay, you know what I mean, tell me of your culture, your ways, your Medicine,” I responded.

At the word Medicine the smile faded a bit, he looked pensive for a moment before saying, “Are you interested in our culture, in our Medicine?”

“Damn right I am,” was my retort. I wanted to learn as much as possible from all the people I met on my travels. I considered the road my college and the people I met my professors.

“Well”, he said, “the first thing you’ve got know is never trust an Indian when he is speaking in his native tongue.” I asked him what he meant. He then told me how when the film companies come looking for extras to play Indians in Westerns the young men are always selected to play any speaking roles that may be in the script for Indians. He explained to me that a few years back one of his brothers had two lines of dialogue in a movie. He said the way it works is that the assistant director is in charge of the “Indians,” and he will invariably tell those with speaking parts to, “Speak Indian when I wave my arms.” When asked by the actor/Indian what he should say, the AD will tell him, “Say anything, it doesn’t matter, no one is going to know what you’re saying anyway.” So, in what has become kind of a custom, the actor/Indian will insult the white man to his face. They always use the dirtiest words of their language. His brother looked the general straight in the eye as he told him, “Your mother is a whore, I have slept with her many times as your father looked on.” Jimmy went on to say that whenever a Western is playing at the Central Heights drive in, he and his friends pile into their pickups and go to the movies. And when an Indian speaks Na-Déné, the language of the Apache, they all laugh uproariously, great fun!

I told Jimmy that was an interesting tidbit, but wasn’t what I had in mind. He just smiled and told me he would fill me in during dinner, which was good timing because just then his grandmother put down a plate of rice and beans before each of us, and a plate of corn tortillas between us.

As we ate, Jimmy, slowly at first, began to tell me not of the Apache, but of his life. Both his parents were dead, they had died from liver disease, “Which is a fancy word for alcoholism,” he added. He had two brothers, both trying their hardest to follow in their parents footsteps. He, on the other hand had sworn never to touch the stuff, not only because of what it had done to his parents, but because of what it had done to the Indian Nation as a whole. He told me that in some tribes the rate of alcoholism was over 80%!

He had gone to college on a scholarship, but had dropped out during the second year. “They don’t teach you to think in those schools. They fill your mind with information and have you regurgitate it back to them in the form of ‘tests’. The information never stays with you, so what’s the point. If they only had a course in deductive reasoning, I might have stayed.”

Jimmy went on to say, “Take History for example. When studying the War in the Pacific we were given only the American point-of view. I believe the correct way to tell of history, especially recent history, is to give the perspective of one side for the first half of the course. Then for the remainder of the course, give the other side’s version of events. Even bring in those who lived through that period in history to tell their side of the story or better yet, the participants. Then let the students make up their own minds about history, no tests needed. I mean why did the Japanese attack Pearl Harbor. What did they have to fear from the Americans? They didn’t do it on a lark, I’m sure some hubris was involved; but we were basically told they did it because they were evil.”

About now, Jimmy was getting up a good head of steam as he continued, “And what was the real reason for employing atom bombs on a people already defeated? Once again, we’re given only the American perspective. It would have been productive to hear the history of World War II from the Japanese point-of-view. Oh, and speaking of the Pacific Theater of World War II and Indians, did you know that in the first months of the war the American code was continually broken by the Japanese?”

I told Jimmy, that no, I hadn’t known that. “Well, I’ll tell you how they fixed the problem,” said he. "They got Navajo Indians to speak their language, that’s what they did. The Signal Corp got every Navajo it could lay its hands on assigned to it, and deployed them throughout the Pacific. That was the end of any code problems for the rest of the war.” Thus having said what he wanted to say, Jimmy leaned back and smiled at me with that beautiful smile of his.

After being disillusioned with college, he had decided to learn the Medicine of his people. He told me of his teacher, The Wise One. He had been taught many things by The Wise One, and he would have brought me to his home as soon as we arrived if he had not gotten ill and taken to the White-Man’s hospital. He told me he had not been here when The Wise One was taken away. However, he had heard that he did not want to go, but was forcibly removed from his home. Jimmy then told me that he had subsequently gone to the hospital twice to bring him home, and both times was ejected from the hospital without being allowed to see him. The second time the police were called and he was told that if he returned, he would be arrested. I told Jimmy that I was sorry his teacher had been taken to the hospital; I also did not trust hospitals to get you out alive. One hundred thousand people die in hospitals every year in this country from illnesses that are iatrogenic in origin. The Wise One did indeed seem wise. Jimmy just sat across the table from me and nodded, his mind was somewhere else at that moment. He told me there wasn’t much else he could tell about the Apache, except that was not how they referred to themselves; Apache was a name given to them by the Zuni, it means “enemy.” They call themselves The Denéé (pronounced Dee-nay), which means The People. He said sometimes it’s spelled Diné, but pronounced the same. He went on to tell me that the people of his Nation where also know as Western Apache and that about 6,000 members of The Denéé were living on the reservation at that time (1969).

By now we had finished eating and I picked up my plate to carry it over to the counter, it’s what I always did at home, and Jimmy had made me feel so much at home I guess I forgot myself for a moment. When he saw my intent, he asked me to sit down please, he appreciated what I had in mind, but his grandmother would not understand. It was her work to feed the men, and if a man intruded into her routine that meant he was not pleased with the job she was doing. Therefore, I sat back down and asked Jimmy to tell me more of his people and their ways. He looked me straight in the eye and said, “Why do you want to know these things?” I told him that I had always had an interest in how the other half lived, but this was more than that; from the moment I alighted from the pickup truck and found myself on an Indian Reservation there was an urge, no a passion, to find out as much as possible of The Denéé. Then it became crystal clear, it was not general information I hungered for, but information concerning the religion of the Denéé. I told Jimmy what I had just realized. He said nothing, he just stared at me for what seemed an eternity. He finally roused himself from his thoughts and said, “Our coming together this day may not have been an accident. I was about to leave you for the night because I have plans But now I think I’ll ask you to join me. I will tell you of the history of our people, and of our religion; and if you wish, you may join me in the ceremony I had planned for tonight.”

I was humbled by what Jimmy had just said, and could only muster a meek, “Thank you.”

After a few moments of idle chit chat, Jimmy said, “It’s time to go, follow me.” We stood and I followed him to the door, but stopped suddenly; I had forgotten to thank his grandmother for dinner. I turned to thank her, but she wasn’t there. I mean she was there when we stood, and now she was nowhere to be seen. Jimmy asked what the hold up was, and I told him that I wanted to thank his grandmother for dinner. He just said, “Come, she knows what’s in your heart.”We walked out of his house, if that is what it is called; that is the one question I forgot to ask that night. However, I would receive the answers to all my other questions before that night was over.

I walked with Jimmy about three hundred yards until we could see a small hill, or hillock, a short distance in front of us. It stood no more than fifteen feet above the floor of the desert on which we walked. On the pinnacle of this hill stood the figure of a woman, and as we neared the rise, I could make out a tripod with something hanging from it. We reached the hill and climbed to the top. Once there, I could see that it was a young girl no more than sixteen and not a woman. She was stirring something in a small black kettle with a diameter at the lip of about six inches. It looked like a miniature version of the kettles in which you see witches depicted while stirring their brew. The kettle was suspended from the middle of the tripod, and hung over a small fire. It was getting dark; the sun had just gone below the horizon so I couldn’t make out what was in the kettle.

There were no introductions, Jimmy simply nodded to the girl and sat down at the edge of the rise with his back to her. Once seated, he motioned for me to sit beside him. We were facing west, and as I mentioned, the sun was below the horizon; but, from one end of the horizon to the other, the sky was a brilliant orange and pink color. The clouds were dark gray and had bright orange linings. The rays of the sun shone upwards from below the horizon, broken in places by the clouds. It was the inverse of the pictures you see depicting God as rays of the sun shining through clouds, but instead of the rays being white, these rays were yellow-orange. After a few moments of watching the beautiful display of color granted us, Jimmy turned to me and said, “That is Life Giver.” I thought he meant the sun. He went on to explain that yes, the sun does give us life, but he was referring to what I would call God. Life Giver is represented by the sun in their culture. He then said, “I will now tell you of our creation myth.”

He then spoke these words:

“Is daze naadleeshé, or Changing Woman, lived alone, and was one day inspired to walk up a hill and build a gowa. She then laid in the gowa with her feet facing east, as the Sun came up His rays shone between her legs, and one of His rays went into her. After that, she became pregnant and had a son, Nayé Nazghane, Slayer of Monsters. Later she was impregnated by Water Old Man and gave birth to Tubaadeschine, Born of Water Old Man. Jimmy told me that next to Life Giver, Changing Woman is the deity most honored and respected.” He said all The Denéé were Is dean naadleeshé be chaghaashé, Children Of Changing Woman.

When he had finished neither of us said a word. I was there to learn, and he would speak when he was ready. By now, the stars had started to come out, so I laid back starring up into the darkening sky as Jimmy renewed speaking. He told of how The Wise One had told him of the great Medicine Man, Geronimo, and how when Geronimo was in prison he had dictated a history of The Denéé to a white man. The Wise One told Jimmy if one day he wanted to be a great maker of Medicine, he should memorize the words of Geronimo. Jimmy told me he had done what The Wise One had suggested. And now he would tell me of his people in the words of the great Medicine Man Geronimo. I closed my eyes and listened.

Geronimo:

In the beginning, the world was covered with darkness. There was no sun, no day. The perpetual night had no moon or stars.

There were, however, all manner of beasts and birds. Among the beasts were many hideous, nameless monsters, as well as dragons, lions, tigers, wolves, foxes, beavers, rabbits, squirrels, rats, mice, and all manner of creeping things such as lizards and serpents. Mankind could not prosper under such conditions, for the beasts and serpents destroyed all human offspring.

All creatures had the power of speech and were gifted with reason.

There were two tribes of creatures: the birds or the feathered tribe and the beasts. The former were organized wider, their chief, the eagle.

These tribes often held councils, and the birds wanted light admitted. This the beasts repeatedly refused to do. Finally, the birds made war against the beasts.

The beasts were armed with clubs, but the eagle had taught his tribe to use bows and arrows. The serpents were so wise that they could not all be killed. One took refuge in a perpendicular cliff of a mountain in Arizona, and his eyes may be see in that rock to this day. The bears, when killed, would each be changed into several other bears, so that the more bears the feathered tribe killed, the more there were. The dragon could not be killed, either, for he was covered with four coats of horny scales, and the arrows would not penetrate these. One of the most hideous, vile monsters was proof against arrows, so the eagle flew high up in the air with a round, white stone, and let it fall on this monster's head, killing him instantly. This was such a good service that the stone was called sacred. They fought for many days, but at last, the birds won the victory.

After this war was over, although some evil beasts remained, the birds were able to control the councils, and light was admitted, then mankind could live and prosper. The eagle was chief in this good fight: therefore, his feathers were worn by man as emblems of wisdom, justice, and power.

Among the few human beings that were yet alive was a woman who had been blessed with many children, but these had always been destroyed by the beasts. If by any means she succeeded in eluding the others, the dragon, who was very wise and very evil, would come himself and eat her babes.

After many years, a son of the rainstorm was born to her and she dug for him a deep cave. The entrance to this cave she closed and over the spot built a campfire. This concealed the babe's hiding place and kept him warm. Every day she would remove the fire and descend into the cave, where the child's bed was, to nurse him; then she would return and rebuild the campfire.

Frequently the dragon would come and question her, but she would say, I have no more children; you have eaten all of them.

When the child was larger, he would not always stay in the cave, for he sometimes wanted to run and play. Once the dragon saw his tracks. Now this perplexed and enraged the old dragon, for he could not find the hiding place of the boy; but he said that he would destroy the mother if she did not reveal the child's hiding place. The poor mother was very much troubled; she could not give up her child, but she knew the power and cunning of the dragon, therefore she lived in constant fear.

Soon after this, the boy said that he wished to go hunting. The mother would not give her consent. She told him of the dragon, the wolves, and serpents; but he said, tomorrow I go.

At the boy's request, his uncle, who was the only man then living, made a little bow and some arrows for him, and the two went hunting the next day. They trailed the deer far up the mountain and finally the boy killed a buck. His uncle showed him how to dress the deer and broil the meat. They broiled two hindquarters, one for the child, and one for his uncle. When the meat was done, they placed it on some bushes to cool. Just then the huge form of the dragon appeared. The child was not afraid, but his uncle was so dumb with fright that he did not speak or move.

The dragon took the boy's parcel of meat and went aside with it. He placed the meat on another bush and seated himself beside it. Then he said, This is the child I have been seeking. Boy, you are nice and fat, so when I have eaten this venison I shall eat you. The boy said, No, you shall not eat me, and you shall not eat that meat. So he walked over to where the dragon sat and took the meat back to his own seat. The dragon said, I like your courage, but you are foolish; what do you think you could do? Well, said the boy, I can do enough to protect myself, as you may find out. Then the dragon took the meat again, and then the boy retook it. Four times in all the dragon took the meat, and after the fourth time the boy replaced the meat he said, Dragon, will you fight me? The dragon said, Yes, in whatever way you like. The boy said, I will stand one hundred paces distant from you and you may have four shots at me with your bow and arrows, provided that you will then exchange places with me and give me four shots. Good, said the dragon. Stand up.

Then the dragon took his bow, which was made of a large pine tree. He took four arrows from his quiver; they were made of young pine tree saplings, and each arrow was twenty feet in length. He took deliberate aim, but just as the arrow left the bow the boy made a peculiar sound and leaped into the air. Immediately the arrow was shivered into a thousand splinters, and the boy was seen standing on the top of a bright rainbow over the spot where the dragon's aim had been directed. Soon the rainbow was gone and the boy was standing on the ground again. Four times this was repeated, then the boy said, Dragon, stand here: it is my time to shoot. The dragon said, All right, your little arrows cannot pierce my first coat of horn, and I have three other coats, shoot away. The boy shot an arrow, striking the dragon just over the heart, and one coat of the great horny scales fell to the ground. The next shot another coat, and then another, and the dragon's heart was exposed. Then the dragon trembled, but could not move. Before the fourth arrow was shot the boy said, Uncle, you are dumb with fear; you have not moved; come here or the dragon will fall on you. His uncle ran toward him. Then he sped the fourth arrow with true aim, and it pierced the dragon's heart. With a tremendous roar the dragon rolled down the mountainside, down four precipices into a canyon below.

Immediately storm clouds swept the mountains, lightning flashed, thunder rolled, and the rain poured. When the rainstorm had passed, far down in the canyon below, they could see fragments of the huge body of the dragon lying among the rocks, and the bones of this dragon may still be found there.

This boy's name was Ndéén. Usen taught him how to prepare herbs for medicine, how to hunt, and how to fight. He was the first chief of the Indians and wore the eagle's feathers as the sign of justice, wisdom, and power. To him and to his people, as they were created, Usen gave homes in the land of the West. They were The Denéé.

I, Geronimo, was born in Nodoyohn Canyon, Arizona, June 1829.

| In that country which lies around the head waters of the Gila River, I was reared. This range was our fatherland; among these mountains our wigwams were hidden; the scattered valleys contained our fields; the boundless prairies, stretching away on every side, were our pastures; the rocky caverns were our burying places.

I was fourth in a family of eight children, four boys and four girls. Of that family, only myself, my brother, Porico, and my sister, Nahdaste , are yet alive. We are held as prisoners of war in this Military Reservation. As a babe I rolled on the dirt floor of my father's tepee, hung in my tsoch at my mother's back, or suspended from the bough of a tree. I was warmed by the sun, rocked by the winds, and sheltered by the trees as other Indian babes. When a child, my mother taught me the legends of our people; taught me of the sun and sky, the moon and stars, the clouds and storms. She also taught me to kneel and pray to Usen for strength, health, wisdom, and protection. We never prayed against any person, but if we had aught against any individual we ourselves took vengeance. We were taught that Usen does not care for the petty quarrels of men. My father had often told me of the brave deeds of our warriors, of the pleasures of the chase, and the glories of the warpath. With my brothers and sisters I played about my father's home. Sometimes we played at hide-and-seek among the rocks and pines; sometimes we loitered in the shade of the cottonwood trees or sought the shudock while our parents worked in the field. Sometimes we played that we were warriors. We would practice stealing upon some object that represented an enemy, and in our childish imitation often perform the feats of war. Sometimes we would hide away from our mother to see if she could find us, and often when thus concealed, go to sleep and perhaps remain hidden for many hours. When we were old enough to be of real service, we went to the field with our parents: not to play, but to toil. When the crops were to be planted we broke the ground with wooden hoes. We planted the corn in straight rows, the beans among the corn, and the melons and pumpkins in irregular order over the field. We cultivated these crops as there was need. Our field usually contained about two acres of ground. The fields were never fenced. It was common for many families to cultivate land in the same valley and share the burden of protecting the growing crops from destruction by the ponies of the tribe, or by deer and other wild animals. Melons were gathered as they were consumed. In the autumn pumpkins and beans were gathered and placed in bags or baskets; ears of corn were tied together by the husks, and then the harvest was carried on the backs of ponies up to our homes. Here the corn was shelled, and all the harvest stored away in caves or other secluded places to be used in winter. We never fed corn to our ponies, but if we kept them up in the wintertime we gave them fodder to eat. We had no cattle or other domestic animals except our dogs and ponies. We did not cultivate tobacco, but found it growing wild. This we cut and cured in autumn, but if the supply ran out, the leaves from the stalks left standing served our purpose. All Indians smoked, men and women. No boy was allowed to smoke until he had hunted alone and killed large game, wolves and bears. Unmarried women were not prohibited from smoking, but were considered immodest if they did so. Nearly all matrons smoked. Besides grinding the corn for bread, we sometimes crushed it and soaked it, and after it had fermented, made from this juice a tiswin, which had the power of intoxication, and was very highly prized by the Indians. This work was done by the squaws and children. When berries or nuts were to be gathered the small children and the squaws would go in parties to hunt them, and sometimes stay all day. When they went any great distance from camp they took ponies to carry the baskets. I frequently went with these parties, and upon one of these excursions a woman named Chokole got lost from the party and was riding her pony through a thicket in search of her friends. Her little dog was following as she slowly made her way through the thick underbrush and pine trees. All at once a grizzly bear rose in her path and attacked the pony. She jumped off, and her pony escaped, but the bear attacked her, so she fought him the best she could with her knife. Her little dog, by snapping at the bear's heels and distracting his attention from the woman, enabled her for some time to keep pretty well out of his reach. Finally the grizzly struck her over the head, tearing off almost her whole scalp. She fell, but did not lose consciousness, and while prostrate struck him four good licks with her knife, and he retreated. After he had gone she replaced her torn scalp and bound it up as best she could, then she turned deathly sick and had to lie down. That night her pony came into camp with his load of nuts and berries, but no rider. The Indians hunted for her, but did not find her until the second day. They carried her home, and under the treatment of their Medicine Men all her wounds were healed. The Indians knew what herbs to use for Medicine, how to prepare them, and how to give the Medicine. This they had been taught by Usen in the beginning, and each succeeding generation had men who were skilled in the art of healing. In gathering the herbs, in preparing them, and in administering the Medicine, as much faith was held in prayer as in the actual effect of the Medicine. Usually about eight persons worked together in make Medicine, and there were forms of prayer and incantations to attend each stage of the process. Four attended to the incantations, and four to the preparation of the herbs. Some of the Indians were skilled in cutting out bullets, arrowheads, and other missiles with which warriors were wounded. I myself have done much of this, using a common dirk or butcher knife. Small children wore very little clothing in winter and none in the summer. Women usually wore a primitive skirt, which consisted of a piece of cotton cloth fastened about the waist, and extending to the knees. Men wore breechcloths and moccasins. In winter they had shirts and legging in addition. Frequently when the tribe was in camp a number of boys and girls, by agreement, would steal away and meet at a place several miles distant, where they could play all day free from tasks. They were never punished for these frolics; but if their hiding places were discovered they were ridiculed. To celebrate each noted event, a feast and dance would be given. Perhaps only our own people, perhaps neighboring tribes would be invited. These festivities usually lasted for about four days. By day we feasted, by night under the direction of some chief we danced. The music for our dance was singing led by the warriors, and accompanied by beating the esadadedné. No words were sung only the tones. When the feasting and dancing were over we would have horse races, foot races, wrestling, jumping, and all sorts of games. Among these games the most noted was the tribal game of Kah. It is played as follows: Four moccasins are placed about four feet apart in holes in the ground, dug in a row on one side of the camp, and on the opposite side a similar parallel row. At night a campfire is started between these two rows of moccasins, and the players are arranged on sides, one or any number on each side. The score is kept by a bundle of sticks, from which each side takes a stick for every point won. First one side takes the bone, puts up blankets between the four moccasins and the fire so that the opposing team cannot observe their movements, and then begin to sing the legends of creation. The side having the bone represents the feathered tribe, the opposite side represents the beasts. The players representing the birds do all the singing, and while singing hide the bone in one of the moccasins, then the blankets are thrown down. They continue to sing, but as soon as the blankets are thrown down, the chosen player from the opposing team, armed with a war club, comes to their side of the campfire and with his club strikes the moccasin in which he thinks the bone is hidden. If he strikes the right moccasin, his side gets the bone, and in turn represents the birds, while the opposing team must keep quiet and guess in turn. There are only four plays; three that lose and one that wins. When all the sticks are gone from the bundle the side having the largest number of sticks is counted winner. This game is seldom played except as a gambling game, but for the purpose it is the most popular game known to the tribe. Usually the game lasts four or five hours. It is never played in daytime. After the games are all finished the visitors say, We are satisfied, and the camp is broken up. I was always glad when the dances and feasts were announced. So were all the other young people. Our life also had a religious side. We had no churches, no religious organizations, no Sabbath day, no holidays, and yet we worshiped. Sometimes the whole tribe would assemble to sing and pray; sometimes a smaller number, perhaps only two or three. The songs had a few words, but were not formal. The singer would occasionally put in such words as he wished instead of the usual tone sound. Sometimes we prayed in silence; sometimes each one prayed aloud; sometimes an aged person prayed for all of us. At other times one would rise and speak to us of our duties to each other and to Usen. Our services were short. When disease or pestilence abounded we were assembled and questioned by our leaders to ascertain what evil we had done, and how Usen could be satisfied. Sometimes sacrifice was deemed necessary. Sometimes the offending one was punished. If any one off the Denéé had allowed his aged parents to suffer for food or shelter, if he had neglected or abused the sick, if he had profaned our religion, or had been unfaithful, he might be banished from the tribe. The Denéé had no prisons as white men have. Instead of sending their criminals into prison they sent them out of their tribe. These faithless, cruel, lazy, or cowardly members of the tribe were excluded in such a manner that they could not join any other tribe. Neither could they have any protection from our unwritten tribal laws. Frequently these outlaw Indians banded together and committed depredations which were charged against the regular tribe. However, the life of an outlaw Indian was a hard lot, and their bands never became very large; besides, these bands frequently provoked the wrath of the tribe and secured their own destruction. When I was about eight or ten years old I began to follow the chase, and to me this was never work. Out on the prairies, which ran up to our mountain homes, wandered herds of deer, antelope, elk, and buffalo, to be slaughtered when we needed them. Usually we hunted buffalo on horseback, killing them with arrows and spears. Their skins were used to make tepees and bedding; their flesh, to eat. It required more skill to hunt the deer than any other animal. We never tried to approach a deer except against the wind. Frequently we would spend hours in stealing upon grazing deer. If they were in the open we would crawl long distances on the ground, keeping a weed or brush before us, so that our approach would not be noticed. Often we could kill several out of one herd before the others would run away. Their flesh was dried and packed in vessels, and would keep in this condition for many months. The hide of the deer soaked in water and ashes and the hair removed, and then the process of tanning continued until the buckskin was soft and pliable. Perhaps no other animal was more valuable to us than the deer. In the forests and along the streams were many wild turkeys. These we would drive to the plains, then slowly ride up toward them until they were almost tired out. When they began to drop and hide we would ride in upon them and, by swinging from the side of our horses, catch them. If one started to fly we would ride swiftly under him and kill him with a short stick, or hunting club. In this way we could usually get as many wild turkeys as we could carry home on a horse. There were many rabbits in our range, and we also hunted them on horseback. Our horses were trained to follow the rabbit at full speed, and as they approached them we would swing from one side of the horse and strike the rabbit with our hunting club. If he was too far away we would throw the stick and kill him. This was great sport when we were boys, but as warriors we seldom hunted small game. There were many fish in the streams, but as we did not eat them, we did not try to catch or kill them. Small boys sometimes threw stones at them or shot at them for practice with their bows and arrows. Usen did not intend snakes, frogs, or fishes to be eaten. I have never eaten of them. There were many eagles in the mountains. These we hunted for their feathers. It required great skill to steal upon an eagle, for besides having sharp eyes, he is wise and never stops at any place where he does not have a good view of the surrounding country. I have killed many bears with a spear, but was never injured in a fight with one. I have killed several mountain lions with arrows, and one with a spear. Both bears and mountain lions are good for food and valuable for their skin. When we killed them we carried them home on our horses. We often made quivers for our arrows from the skin of the mountain lion. These were very pretty and very durable. During my minority we had never seen a missionary or a priest. We had never seen a white man. Thus quietly lived the Bedonkohe. In the summer of 1858, being at peace with the Mexican towns as well as with all the neighboring Indian tribes, we went south into Old Mexico to trade. Our whole tribe went through Sonora toward Casa Grande, our destination, but just before reaching that place we stopped at another Mexican town called by the Indians Kaskiyeh. Here we stayed for several days, camping outside the city. Every day we would go into town to trade, leaving our camp under the protection of a small guard so that our arms, supplies, and women and children would not be disturbed during our absence. Late one afternoon when returning from town we were met by a few women and children who told us that Mexican troops from some other town had attacked our camp, killed all the warriors of the guard, captured all our ponies, secured our arms, destroyed our supplies, and killed many of our women and children. Quickly we separated, concealing ourselves as best we could until nightfall, when we assembled at our appointed place of rendezvous, a thicket by the river. Silently we stole in one by one: sentinels were placed, and, when all were counted, I found that my aged mother, my young wife, and my three small children were among the slain. There were no lights in camp, so without being noticed I silently turned away and stood by the river. How long I stood there I do not know, but when I saw the warriors arranging for a council I took my place. That night I did not give my vote for or against any measure; but it was decided that as there were only eighty warriors left, and as we were without arms or supplies, and were furthermore surrounded by the Mexicans far inside their own territory, we could not hope to fight successfully. So our chief, Mangus-Colorado, gave the order to start at once in perfect silence for our homes in Arizona, leaving the dead upon the field. I stood until all had passed, hardly knowing what I would do. I had no weapon, nor did I hardly wish to fight, neither did I contemplate recovering the bodies of my loved ones, for that was forbidden. I did not pray, nor did I resolve to do anything in particular, for I had no purpose left. I finally followed the tribe silently, keeping just within hearing distance of the soft noise of the feet of the retreating Denéé. The next morning some of the Indians killed a small amount of game and we halted long enough for the tribe to cook and eat, when the march was resumed. I had killed no game, and did not eat. During the first march as well as while we were camped at this place I spoke to no one and no one spoke to me, there was nothing to say. For two days and three nights we were on forced marches, stopping only for meals, then we made a camp near the Mexican border, where we rested two days. Here I took some food and talked with the other Indians who had lost in the massacre, but none had lost as I had, for I had lost all. Within a few days we arrived at our own settlement. There were the decorations that Alope had made, and there were the playthings of our little ones. I burned them all, even our tepee. I also burned my mother's tepee and destroyed all her property. I was never again contented in our quiet home. True, I could visit my father's grave, but I had vowed vengeance upon the Mexican troopers who had wronged me, and whenever I came near his grave, or saw anything to remind me of former happy days my heart would ache for revenge upon Mexico. As soon as we had again collected some arms and supplies Mangus-Colorado, our chief, called a council and found that all our warriors were willing to take the warpath against Mexico. I was appointed to solicit the aid of other tribes in this war. When I went to the Chokonen, Cochise, their chief, called a council at early dawn. Silently the warriors assembled at an open place in a mountain dell and took their seats on the ground, arranged in rows according to their ranks. Silently they sat smoking. At a signal from the chief I arose and presented my cause as follows: "Kinsman, you have heard what the Mexicans have recently done without cause. You are my relatives, uncles, cousins, brothers. We are men the same as the Mexicans are, we can do to them what they have done to us. Let us go forward and trail them, I will lead you to their city; we will attack them in their homes. I will fight in the front of the battle. I only ask you to follow me to avenge this wrong done by these Mexicans, will you come? It is well, you will all come. Remember the rule in war, men may return or they may be killed. If any of these young men are killed I want no blame from their kinsmen, for they themselves have chosen to go. If I am killed no one need mourn for me. My people have all been killed in that country, and I, too, will die if need be." I returned to my own settlement, reported this success to my chieftain, and immediately departed to the southward into the land of the Nedni. Their chief, Whoa, heard me without comment, but he immediately issued orders for a council, and when all were ready gave a sign that I might speak. I addressed them as I had addressed the Chokonen tribe, and they also promised to help us. It was in the summer of 1859, almost a year from the date of the massacre of Kaskiyeh, that these three tribes were assembled on the Mexican border to go upon the warpath. Their faces were painted, the war bands fastened upon their brows their long scalp-locks ready for the hand and knife of the warrior who would overcome them. Their families had been hidden away in a mountain rendezvous near the Mexican border. With these families a guard was posted, and a number of places of rendezvous designated in case the camp should be disturbed. When all were ready the chieftains gave command to go forward. None of us were mounted and each warrior wore moccasins and also a cloth wrapped about his loins. This cloth could be spread over him when he slept, and when on the march would be ample protection as clothing. In battle, if the fight was hard, we did not wish much clothing. Each warrior carried three days' rations, but as we often killed game while on the march, we seldom were without food. We traveled in three divisions: the Bedonheko led by Mangus-Colorado, the Chokonen by Cochise, and the Nedni by Whoa; however, there was no regular order inside the separate tribes. We usually marched about fourteen hours per day, making three stops for meals, and traveling forty to forty-five miles a day. I acted as guide into Mexico, and we followed the river courses and mountain ranges because we could better thereby keep our movements concealed. We entered Sonora and went southward past Quitaro, Nacozari, and many smaller settlements. When we were almost at Arispe we camped, and eight men rode out from the city to parley with us. These we captured, killed, and scalped. This was to draw the troops from the city, and the next day they came. The skirmishing lasted all day without a general engagement, but just at night we captured their supply train, so we had plenty of provisions and some more guns. That night we posted sentinels and did not move our camp, but rested quietly all night, for we expected heavy work the next day. Early the next morning the warriors were assembled to pray, not for help, but that they might have health and avoid ambush or deceptions by the enemy. As we had anticipated, about ten o'clock in the morning the whole Mexican force came out. There were two companies of cavalry and two of infantry. I recognized the cavalry as the soldiers who had killed my people at Kaskiyeh. This I told to the chieftains, and they said that I might direct the battle. I was no chief and never had been, but because I had been more deeply wronged than others, this honor was conferred upon me, and I resolved to prove worthy of the trust. I arranged the Indians in a hollow circle near the river, and the Mexicans drew their infantry up in two lines, with the cavalry in reserve. We were in the timber, and they advanced until within about four hundred yards, when they halted and opened fire. Soon I led a charge against them, at the same time sending some braves to attack the rear. In all the battle I thought of my murdered mother, wife, and babies; of my father's grave and my vow of vengeance, and I fought with fury. Many fell by my hand, and constantly I led the advance. Many braves were killed The battle lasted about two hours. At the last four Indians were alone in the center of the field, myself and three other warriors. Our arrows were all gone, our spears broken off in the bodies of dead enemies. We had only our hands and knives with which to fight, but all who had stood against us were dead. Then two armed soldiers came upon us from another part of the field. They shot down two of our men and we, the remaining two, fled toward our own warriors. My companion was struck down by a saber, but I reached our warriors, seized a spear, and turned. The one who pursued me missed his aim and fell by my spear. With his saber I met the trooper who had killed my companion and we grappled and fell. I killed him with my knife and quickly rose over his body, brandishing his saber, seeking for other troopers to kill. There were none. But the Denéé had seen. Over the bloody field, covered with the bodies of Mexicans, rang the fierce Denéé war-whoop. Still covered with the blood of my enemies, still holding my conquering weapon, still hot with the joy of battle, victory, and vengeance, I was surrounded by the Denéé braves and made war chief of all the Denéé. Then I gave orders for scalping the slain. I could not call back my loved ones, I could not bring back the dead Denéé, but I could rejoice in this revenge. The Denéé had avenged the massacre of Kaskiyeh. Life Giver: It seemed like many minutes from the time Jimmy stopped talking until I realized there was no more to come. Actually, it was probably only a few seconds. But, he was silent; it was as if he had run out of words. Once I did realize the story of Geronimo was finished, I was hesitant to open my eyes; I did not want to break the spell. Though eventually I did open my eyes and looked right into the face of God! It was the stars! While Jimmy was talking, the sun had traveled to the other side of the world and the stars had come out. Never had I seen anything like it. For three hundred and sixty degrees the stars touched the horizon. There was no light to impede their brilliance, no buildings to block my view of that wondrous sight. There was just as much starlight as there was black sky. I felt as though I could reach out and touch them, they seemed that close. I could see how Ptolemy believed the earth was encapsulated within crystalline spheres. In the dry desert air the stars did indeed look as though they were made of fine, delicate crystal. I saw The Great Bear, and Polaris, the only star that does not move. Orion seemed as though he could lower his arm and smite me with his club. I was in the mist of searching for other constellations when Jimmy broke my reverie. He said, “It’s time.” As I sat up, the young girl handed me a wooden bowl, Jimmy was already holding one exactly like it. We each held our bowls with two hands in front of us, about chest high. I was told by Jimmy that the potion would help me go within, to commune with the Old Ones. “It is my hope to speak with Life Giver at times like these, but it has not happened yet. The Wise One tells me to be patient that he has only spoken to Life Giver once, though he has spoken with Changing Woman many times.” I said nothing. Jimmy reached his bowl towards me as in a toast. I did the same and then we drank whatever concoction was in those bowls. Jimmy told me that we would not speak again until morning. He would continue facing west, and that I should face north. I walked ninety degrees around the rise to Jimmy’s right, sat down and awaited what was to come. It was starting to get a little cool, and I thought it would have been nice if had the forethought to bring a jacket. In an effort to keep warm I brought my knees up to my chest, folded my arms about them and rested my chin on my knees. I looked around to see what the girl was up to, but she, like the grandmother, was gone. I had nothing else to do but settle in and wait for the Old Ones. Time started to stretch out, a second felt like a minute; Einstein was right. After awhile I noticed I wasn’t cold any longer. I unfolded myself and lay back to look at the stars. As I said, time was playing tricks on me. I don’t know how long it was after I lay back that I heard the voice. At first I thought it was Jimmy, but when I looked in his direction he was staring off into the western sky oblivious of me and his surroundings. As I was looking towards Jimmy I heard it again. It was in my head, and the voice was calling to me, but not by name. Aloud I said, “Are you calling me?” The voice responded: “There is no need to use your vocal cords, think and I will hear you. For some reason this all seemed perfectly natural, as though I spoke with disembodied entities every day. My first or I guess if you want to be technical, my second question was, “Who are you?” I swear this is what I heard, “I have many names, and have had many other names in the past. I am known to your friend Jimmy as Life Giver, I am known to you and your culture as God. Some refer to me as Jehovah, and I am called Allah and Krishna by others.” I don’t know why, but for some reason it did not seem strange that I was having a conversation with God. The next thing I said, or thought, or whatever, was, “If you are who you say you are, why do you speak with me when Jimmy has desperately and earnestly been trying to speak with you for years?” I heard this reply: “I have been with Jimmy all those years, and more, waiting for him to notice me. I am with my children, all my children, always. I am never not with you.”

NOTE: In an effort to cut down on the prose, I offer a transcript of my conversation with the entity, which I have come to believe was indeed who It claimed to be, Life Giver. Before you make up your mind read the transcript in its entirety then decide.